Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Vestibulum maximus, lorem tincidunt ornare rhoncus, justo felis semper turpis, consectetur eleifend nunc magna vitae nibh.

Article Title Article Title

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Vestibulum maximus, lorem tincidunt ornare rhoncus, justo felis semper turpis, consectetur eleifend nunc magna vitae nibh.

NOTE: This is just a digest of the Mojares Panel report on the issue of the 1521 Easter Sunday Mass. Access the full report and related documents from the National Historical Commission of the Philippines here.

The National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP) received multiple claims as to where the site of the 1521 Easter Sunday Mass was: some say it was in Masao or in Pinamanculan, both are neighboring barangays in the highly historic Butuan City; others claim it was in Baug, Magallanes, Agusan del Norte (which was the former town proper of Butuan; actually, the Spaniards erected a monument here in 1872 commemorating the “First Mass”).

Since 1921, the Philippine government recognizes Limasawa, an island municipality of the Province of Southern Leyte, as the site of the event, based on the stand of the Committee for the IV Centenary of the Discovery of the Philippines created by the U.S. Insular Government of the Philippine Islands. It was further recognized through a historical marker by the Philippines Historical Committee (forerunner of the NHCP) installed in Limasawa in 1950 and a new one on 31 March 2021 in Barangay Triana, at the west side of the island. The National Historical Institute and its successor NHCP constituted four panels to settle the historical issue (i.e., 1980 Samuel Tan Workshop, 1995 Justice Emilio Gancayco Panel, 2008 Benito Legarda Panel, 2019 Resil Mojares Panel)—all reaffirmed the historicity of Limasawa. Section 5(e) of the Republic Act No. 10086 or the NHCP Charter mandates the agency to “actively engage in the settlement or resolution of controversies or issues relative to historical personages, places, dates and events.” The recent decision of the NHCP, formalized through NHCP Board Resolution No. 2 signed on 15 July 2020, was further supported by the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines (CBCP) through a statement of CBCP Church History Team to the Mojares Panel issued on 26 February 2021.

The Term “First Mass”

Before it constituted the Mojares Panel in November 2019, the NHCP and CBCP agreed to adopt the term “Easter Sunday Mass” to refer to the Christian mass celebrated on 31 March 1521 in the highly contentious place called Mazaua. This is to not preempt other possible Christian masses prior to 31 March 1521. This was adopted by the National Quincentennial Committee in its promotions and publications, in print and online.

Error in Reading Butuan

Note: Primary sources are firsthand accounts of those who witnessed the event or close to the event as it happened. Whereas, secondary sources were written by non-witnesses based on the narratives of firsthand accounts or by interviewing eyewitnesses; contents are verifiable by revisiting the primary sources.

For almost 300 years, Spaniards and Filipinos believed the 1521 Easter Sunday Mass happened in Butuan—not until scholars had full access to one of the four extant manuscripts of Pigafetta’s chronicle of the Magellan-Elcano expedition in 1800: the Italian text archived in the Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, Italy, which mentions nothing about Butuan as the site of the 1521 Easter Sunday Mass but Mazaua. In 1895, the Ambrosiana copy of Pigafetta’s was published in its original language for the first time. This gave Filipino linguist and philologist Trinidad H. Pardo de Tavera the opportunity to verify that indeed there was no mention of Butuan in Pigafetta’s chronicle and since then began recognizing Limasawa as the logical Mazaua.

Historian Fr. Pablo Pastells, SJ, who was among the teachers of Jose Rizal at Ateneo de Municipal de Manila (now the Ateneo de Manila University), corrected his predecessor Jesuit historians and chroniclers like Fr. Francisco Colin, SJ who proliferated the error for centuries. Fr. Miguel Bernad, SJ, another Jesuit historian, traced the earliest known source of attributing Butuan as the site of the 1521 Easter Sunday to the summarized version of Pigafetta’s chronicle published in Gian Battista Ramusio’s 1550 three-volume work, Delle navigationi et viaggi (a secondary source already). Eminent Philippine historian William Henry Scott, who supported Fr. Bernad’s criticism to Butuan, observed that “Ramusio edition shows… to be a paraphrase rather than a translation—and a poor one.” It is because Ramusio confused the volunteering of Siaui, the rajah of Butuan who visited Mazaua, of bringing Magellan and Pigafetta to the Trinidad, the flagship of the expedition anchored off the island, after a feast hosted by Colambu, the rajah of Mazaua and a sibling of Siaui of Butuan. What Ramusio wrote was that Magellan was in Butuan and Siaui accompanied to Butuan Magellan’s men who were in Trinidad—and succeeding this story is already about the 1521 Easter Sunday Mass. Ramusio also garbled the characters.

|

Pigafetta’s Text |

Ramusio’s Text |

| “When dawn broke, the king (Colambu of Mazzaua—NQC) came and took me by the hand, and so we went to the same place where we had dined to partake in breakfast (in Mazzaua—NQC), but this time the small boat came to pick us up (to be brought to the flagship, Trinidad—NQC). Before we left, the king joyfully kissed our hands as we did his. A brother of his (Siaui—NQC), who was the king of another island (Butuan and Calaghan—NQC), and three of his men came to accompany us (to the flagship—NQC). The captain general kept him to dine with us and gave him many gifts.

“In the island of this king who came to our ships one can find pieces of gold, of the size of walnuts and eggs, abundantly covering the land… His island is called Butuan and Calagan.” |

“The Prince departed at the break of dawn, but as ours were getting up, a brother of his came to find them, and they accompanied him to an island where the Captain was, who kept them to dine with them and gave many presents to him and all those with him.

“In that island where the King came to see our ship, big pieces of gold were found… These islands are called Buthuan and Calaghan.” |

Ramusio’s work influenced generations of writers. But as the discipline of History develops through time, students are trained to discern what is primary from secondary and that one must put a premium to the former and be critical of the sources and provenance of the latter. With this, historians who supported Limasawa instead of Butuan have just exercised the basic historical methodology of tracing the primary source and scrutinizing its provenance vis-à-vis recognized Pigafetta over Ramusio, Colin, etc. Citing secondary sources or non-contemporaneous, non-eyewitness accounts in supporting Butuan as the site of the 1521 Easter Sunday Mass is dead-end.

Primary Sources Matter

There is this misconception that documents written during the Spanish period are considered primary sources because they are basically Spanish. Some of the Butuan proponents argued that the following Spanish sources mention Butuan as the site of the 1521 Easter Sunday Mass are valid sources: 1581 edict of Bishop Domingo Salazar in the Anales ecclesiasticos de Filipinas 1574-1683, the 1886 Breve reseña de diocesis de Cebu, Fr. Francisco Colin’s Labor evangélica: Ministerios apostolicos de los obreros de la Compaña de Jesus (1663), Fr. Francisco Combés’ Historia de Mindanao y Jolo (1667), Fray Gaspar de San Agustin’s Conquistas de las Islas Filipinas (1698), the 1872 monument in Magallanes, Agusan del Norte, and a few other accounts written by American authors in the early part of the 20th century.

There are countless non-primary or non-contemporaneous sources pertaining to Butuan as the site of the 1521 Easter Sunday Mass. But, as already said in the preceding slide, for almost 300 years, Spaniards and Filipinos believed the 1521 Easter Sunday Mass happened in Butuan—not until scholars had full access to one of the four extant manuscripts of Pigafetta’s chronicle of the Magellan-Elcano expedition in 1800: the Italian text archived in the Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, Italy, which mentions nothing about Butuan as the site of the 1521 Easter Sunday Mass but Mazaua. As an iteration, historian Fr. Pablo Pastells, SJ corrected his predecessor Jesuit historians and chroniclers like Fr. Francisco Colin, SJ who proliferated the error for centuries. Fr. Miguel Bernad, SJ, another Jesuit historian, traced the earliest known source of attributing Butuan as the site of the 1521 Easter Sunday to the summarized version of Pigafetta’s chronicle published in Gian Battista Ramusio’s 1550 three-volume work, Delle navigationi et viaggi (a secondary source already).

Again, citing secondary sources or non-contemporaneous, non-eyewitness accounts, where in fact there are solid primary sources available, in supporting Butuan as the site of the 1521 Easter Sunday Mass is dead-end.

Bounds of Reason

Upholding the centuries-old Butuan tradition, most of the anti-Limasawa proponents argue that the Mazaua mentioned by Pigafetta as the site of the 1521 Easter Sunday Mass was actually Masao, Butuan City. They also argued that compared to Limasawa, Masao is closer in spelling to what ‘primary sources’ mention (i.e., Mazaua). In toponomy (interdisciplinary study of the origin of place names using linguistics, history, archaeology, anthropology, geology, and geography, among others), archival spellings are not taken at face value. It is toponymically erroneous to claim that Zzamal, Humunu, and Zzubu were the ‘original’ names of Samar, Homonhon, and Cebu only because it was how Pigafetta spelled them. One can collect as many spelling variations of Mazaua from 16th-century primary and secondary sources (including maps), but these must undergo the scrutiny of toponymical methodology. It is still the descriptions of the island of Mazaua that matter.

The Mojares Panel scrutinized the coordinates of Mazaua given by the eyewitnesses and compared them with contemporary measurements. Pigafetta recorded it at 9 2/3 or 9º40’N latitude, Francisco Albo, another eye witness, placed it at 9 1/3 or 9º20’N latitude, and the Genoese Pilot, also a primary source, wrote 9 or 9º00’N latitude. The panel cited a study presented in the 16th International Multidisciplinary Scientific Geoconference (Bulgaria, 2016) by a group of experts who compared the coordinates given by Pigafetta with the present coordinates using a computer-based system and the result was 9⁰56’ N latitude or only a 0⁰16’ difference against Pigafetta’s. Even a layman can confirm the coordinates of Limasawa by simply Googling it and the result will be a 9°54’ N latitude. Taking all these pieces of evidence into account, the panel noted that, although the navigational coordinates during this period were just estimates, Pigafetta’s 9º40’N latitude was still closer to Limasawa than to Butuan which, using the modern coordinates, was located at 8°56’ N latitude.

Another argument they developed was that Masao was formerly an ancient island that eventually merged with mainland Butuan. Therefore, the arguments imply that Mazaua was closer to mainland Mindanao for a few miles. But primary sources, at least by Pigafetta, describe nothing about Mindanao, and the way Pigafetta described the island of Butuan and Calaghan, which are definitely in Mindanao, had a certain distance. Assuming that there indeed geological changes that happened between 1521 to the present, the location of Masao, Butuan City is too far from the coordinates given by Pigafetta and Albo and the current reckoning of contemporary experts.

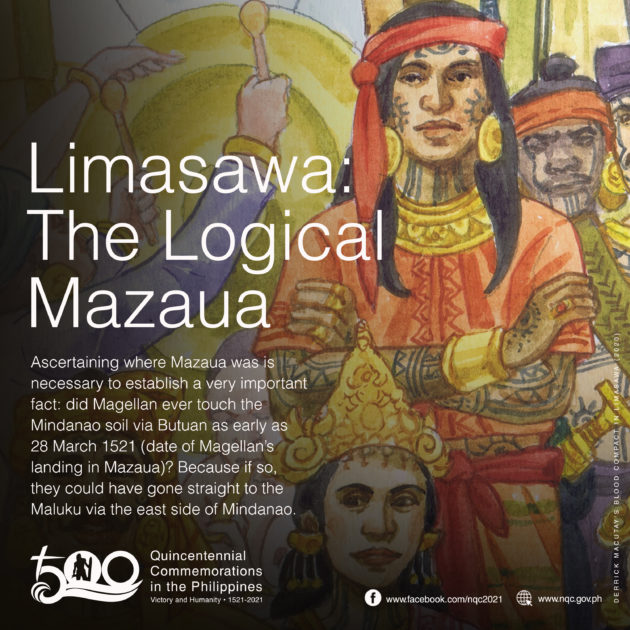

Limasawa: The Logical Mazaua

Pigafetta noted that Mazaua was 25 leagues away from Acquada (i.e., Homonhon). Butuan is already 35.56 leagues (197.95 kms) away from Homonhon (an island in Guiuan, Eastern Samar) compare to Limasawa, which is 23.99 leagues (133.58 kms), thus, close enough to what Pigafetta had recorded. The chronicler also recorded Mazaua at 9 2/3 (9º 40’N latitude in modern reading), Albo placed it at 9 1/3 (9º20’N latitude), and the Genoese Pilot wrote 9 (9º00’N latitude). Even a layman can confirm the coordinates of Limasawa by simply Googling it and the result will be a 9°54’ N latitude. Although the navigational coordinates during his period were just estimates, Pigafetta’s 9º40’N latitude was still closer to Limasawa than to Butuan which, using the modern coordinates, is located at 8°56’ N latitude.

Ascertaining where Mazaua was is necessary to establish a very important fact: did Magellan ever touch the Mindanao soil via Butuan as early as 28 March 1521 (date of Magellan’s landing in Mazaua)? Because if so, they could have gone straight to the Maluku via the east side of Mindanao. Nevertheless, history has it that Magellan became more interested in Cebu, an island ‘northwest’ of Mazaua, upon hearing it from Colambu while in Mazaua.

Almost forty-four years after, on 13 February 1565, Miguel Lopez de Legazpi, head of the Spanish expedition to the “western islands” (later named the Philippines), requested the people of Cabalian (now the Municipality of San Juan, Southern Leyte) if someone could bring him to Mazaua. Legazpi said, “the people there were friends of the Spaniards whereas in other places we had found no friends.” According to the local people, the location of Mazaua from Cabalian “was only leagues away,” implying it was indeed nearby. For centuries, it was believed that the island of Mazaua was part of Butuan, and that later on the island became part of the Mindanao landmass owing to the siltation of Agusan River. While the said natural phenomenon is possible to occur in a delta-like the mouth of Agusan River, Mazaua should be just a few kilometers from mainland Mindanao. But how come the 1565 report implies that Mindanao is quite far from Mazaua (“that the land which they could see from that place [Mazaua] was a point of the island of Vindanao [sic]”). And if Mazaua was in Butuan, why did Legazpi have to pass by Mazaua (from Cabalian on 9 March 1565) in proceeding to Camiguin (“which they could see from there” [Mazaua] on 11 March 1565) to gather cinnamon and then to Butuan (afternoon of 14 March 1565)? From Cabalian, the distance of Butuan is 25.17 leagues (140.1 kms)—too far to be described as “only leagues away.” But Limasawa, an island municipality in Southern Leyte, which most historians think to be the historic Mazaua, is barely 7.43 leagues (41.36 kms) away from Cabalian via Panaon Strait.

On behalf of President Rodrigo Roa Duterte, please accept my warmest congratulations to the Catholic faithful for this milestone. Accept as well the warm greetings from the National Quincentennial Committee chaired by Executive Secretary Salvador Medialdea which yours truly is representing. Despite the pandemic we are facing right now, we are still here marking a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

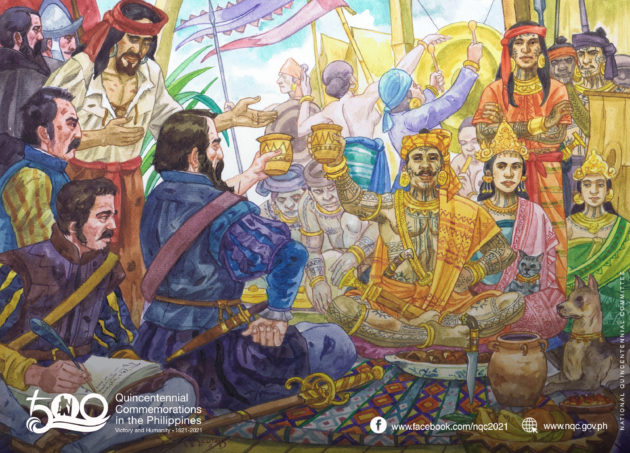

To our ancestors, the period between March 16 and 31, 1521 was an ordinary dry season. But to the foreigners from Spain, who were carried by the current and the wind of the Pacific to Eastern Visayas, it was a Lenten Season. Meaning, it was a period of fasting. When they landed in Philippine soil, especially Homonhon, now under Guiuan, Eastern Samar, it was Sunday of St. Lazarus or the fifth Sunday of Lent. Ferdinand Magellan, a devout Catholic who headed these Spaniards as the captain-general of the Magellan-Elcano expedition, ordered killing a wild boar and indulge their selves in the springs of Homonhon. The following day, March 18, 1521, our ancestors met Magellan for the first time. They gave them food and drinks, even brought them provisions. Then on March 28, 1521, Maundy Thursday, here in Limasawa, Magellan and his crew indulged once again with liquor and other sustenance. Colambu, the Rajah of Limasawa and the most powerful ruler of the Visayas next to the Rajah of Cebu, even ordered serving them with meat.

Did Magellan and his presumably all-Catholic crew break the Catholic custom of fasting? We will further understand this through these words from Antonio Pigafetta, the chronicler of the expedition, to wit:

We were three months and 20 days without getting any kind of fresh food. We ate biscuit, which was no longer biscuit, but powder of biscuits swarming with worms… It stank strongly of the urine of rats. We drank yellow water that had been putrid for many days. We also ate some ox hides that covered the top of the mainyard…

Pigefatta further narrated that they also ate rats on board and that “The gums of both the lower and upper teeth of some of our men swelled, so that they could not eat under any circumstances and therefore died.” “Had not God and His blessed mother given us so good weather we would all have died of hunger in that exceeding vast sea (referring to the Pacific),” the Italian chronicler added.

Here, we see how the almost-dying expedition was saved by our ancestors. They were like Lazarus whom Christ brought back to life. And if not for the compassion and kindness of our ancestors in Guiuan, succeeding events leading to what we are commemorating today will no longer be possible. But will God judge Magellan and his crew for breaking the fasting in 1521? Psalm 75:3 says God “will judge uprightly.” Surely, the Almighty understands that the Magellan-Elcano expedition was deprived for four months of the nutrients an ordinary human needs. God is love (1 John 4:8). As a Christian, I tend to believe that God answered the expedition’s prayers: a calm Pacific and meeting the amazing people—our ancestors.

Our ancestors might not fully know what Easter Sunday means, but for us, the majority of their descendants, that story from 1521 matters a lot. It is symbolic because of all Christian celebrations, our ancestors first acquainted Christ on the day of the latter’s Resurrection. Then our ancestors, through Colambu and his sibling, Siaui, the rajah of Butuan-Calaghan, joined Magellan in erecting a cross atop the highest point of the island, to serve as a reminder of Christ’s presence in this part of the world.

The succeeding generations thereafter had a clearer understanding of Christianity. The faith might be foreign-introduced, but our ancestors loved acquainting various cultures and faiths which for them had value. It just so happened Christianity was so widespread that we owned it and Christ, by process, became us—we identify to his sacrifices and his teachings of loving one’s fellow human being which is pakikipagkapwa in our own culture. But our ancestors would not appreciate Christ if not for the early missionaries who defended them from the atrocities of Spanish officials. Let me borrow the remarks of the Spanish writer Juan Alvarez Guerra in 1898. He said:

The [early missionaries] were all patriots, and the majority of them were gentlemen, liberal and humane. They lived the intimate life of the Indio and everybody set up a family that is more or less spiritual… Anyone would have tried to raise those towns wherein the Indio wholly belonged to the friar and the friar wholly for the Indio! Everybody constituted a family.

Guerra continued:

The confidence that Indio felt for the friar was also reflected in the external manifestation of his faith. In the span of centuries, no other people in the world have celebrated its religious feast with as much magnificence as that of the Indio. All images of the Catholic orb were gathered and the majority of them adorned the Indio homes. There was no commemoration unprepared, a saint not honored, a congregation neglected nor a bell left idle…

Guerra admitted that “If the earlier traditional friar had not disappeared, [the Philippine Revolution] would have been impossible.” But the birthing of the Filipino nation was destined to happen, and we became the first democracy and republic in Asia. And mind you, this republic and democracy were born in Barasoain Church. We even had a Military Chaplain during the First Philippine Republic in the name of Gregorio Aglipay. We cannot distill Christianity out of the Filipino, vice versa. The acceptance of faith and the maladministration that caused the Philippine Revolution should be qualified in their respective context of time. As President Duterte said during the unveiling of the historical marker of Samar for the 500th anniversary of the first circumnavigation of the world on March 18, “We are conscious that it was the reality of the moment at that time.”

In moving forward, history is the ultimate judge. We cannot disown what had happened but learn from it not to happen again vis-à-vis acknowledge what have we become and appreciate our present being.

Anthony Gerard Gonzales is an Undersecretary of the Office of the Presidential Assistant for the Visayas and a member of the National Quincentennial Committee. Speech delivered during the 500th anniversary of the First Easter Mass in the Philippines, Limasawa, Southern Leyte, 31 March 2021.

On 9 April 1521, two days after the Magellan-Elcano expedition reached Cebu, Ferdinand Magellan enticed the rulers of Cebu that to be a Christian was to be an ally of the most powerful king in the world (i.e., Spanish King). According to Antonio Pigafetta, chronicler of Magellan, around 800 of our ancestors in Cebu were baptized as Christians. Among them was the chief of Cebu himself, Rajah Humabon, and his wife, who was christened Juana. Magellan ordered the new converts to destroy their idols and shrines along the shore. To refocus our ancestors’ spiritual life to Christianity, Magellan presented Juana with a 15-centimeter image of the child Jesus, the Santo Niño.

That event in 1521 marked the introduction of Christianity in the Philippines. Eventually, the Philippines became one of the bastions of Christianity in Asia, and the Santo Niño gains a special role in the heart of the Filipinos, particularly among the Roman Catholic faithful.

Devotion to the Santo Niño

The devotion to the Santo Niño in the Philippines flourished spontaneously when the Spaniards led by Miguel Lopez de Legazpi promoted it in 1565. After they captured Cebu on 28 April 1565, the Spaniards discovered the image believed to be the one presented by Magellan in Cebu 44 years earlier. Describing the image as “like those of Flanders,” Legazpi interpreted the discovery as divine providence. Later in their conquest, similar providential discoveries by the Spaniards were made, like in 1571, when they discovered in Manila the image of the Virgin Mary. Historian Ambeth Ocampo is critical of these narratives, saying that the Spaniards could have only justified their presence in this part of the world. For historian Jaime Veneracion, these occurrences in the nascent Spanish colonization were products of their time, when Spain was in the age of mysticism marked by the belief of the Spaniards that their god willed their triumphs.

Contrary to popular belief, Christianization of the Philippines began not in 1521 but in 1565. It was in that year that the first missionaries evangelized Christianity in the archipelago. For historical reckoning, the National Quincentennial Committee branded the 1521 event as the introduction of Christianity in the Philippines. Nonetheless, the first missionaries sustained the reverence of our ancestors in Cebu to the Santo Niño since 1521 by preaching them the Christian faith. From then on, the said missionaries popularized the historic Santo Niño in various parts of the Visayas and Luzon. In fact, the Santo Niño became the patron saint of Tondo, the first Christian parish in Luzon. Even the Christian inhabitants of the Maluku, especially Ternate (both part of Indonesia today), who were evacuated by the Spaniards to Cavite in the mid-17th century, venerated the Santo Niño as their patron saint. Eventually, these people from Ternate established their own town, named after their hometown in Indonesia, and installed their centuries-old Santo Niño from Indonesia as their patron saint.

According to anthropologist Rosa C P. Tenazas, the devotion to the Santo Niño in the Philippines can be divided into two centers: the primary center based in Cebu with influence in Bohol, Leyte, Samar, Negros, and Iloilo; and the secondary centers based in Manila with influence in Tondo, Pandacan, Makati, and Bulacan.

The Filipino in the Santo Niño Devotion

Anthropologist Peter J. Bräunlein explained that the Filipinos’ “affection” for the Santo Niño was brought about by our fondness for children and “rubbing and pinching babies.” This may explain the “rubbed nose and the peeled-off part” of the face of Cebu’s Santo Niño. Also connected to this is our custom of touching or kissing the face, hands, or feet of a sacred image.

Although devotion to the Santo Niño also developed in Europe, particularly in Prague, in the 17th century, the devotion to the Santo Niño in the Philippines is completely organic and local to us, Filipinos. Philippine devotion to the Santo Niño progressed from the fusion of Christianity and the indigenous belief system of our ancestors, the one thing the Spanish missionaries failed to prevent, despite their stern eradication of old unchristian practices. According to Bräunlein:

Starting with the first encounter, the foreign Santo Niño was treated as an orphaned deity. The survival of the image in the indigenous setting, free of missionary control for over 44 years, favored the unique potential of the image to be appropriated and translated into local contexts for diverse spiritual needs and purposes.

Bräunlein’s theory is supported by the reports of Legazpi and his men about the discovery of the image of the Santo Niño in Cebu. It was found placed in a chest full of flowers in a house, proof that it was venerated as a deity by our ancestors. Still, according to Bräunlein, our ancestors “highly appreciated” the Santo Niño after the Magellan-Elcano expedition left because of its “resemblance to the traditional idols, called tao-tao (manikin), bata bata (great-grandparent) or larawan (image, mold, model).” Even the dance for the Santo Niño of Cebu called sinulog, from the root word Cebuano “sulog” or wave, has an ancient flavor. The dance mimics the sea waves to the beat of the drums. The sinulog is a rite for asking favors (sangpit) to the Senyor (nickname of the Santo Niño). While holding a candle, the dancer shouts out the name of the one he or she is dancing for, followed by “Pit Senyor!”

Aside from Cebu, there is also a dance for the Santo Niño in Kalibo, Aklan called ati-atihan derived from the war dance of the Ati, marked by the crying of “hala-bira.” In Pandacan, Manila, the dance for the Santo Niño is called buling-buling.

Devotion and Revolution

Even the Cebuanos’ participation in the Philippine Revolution in 1898 was characterized by the devotion to the Santo Niño. On Palm Sunday, 3 April 1898, around 5,000 Cebuano revolutionaries led by Pantaleon “Leon Kilat” Villegas attacked the Spanish military installation in Cebu, crying “Mabuhi ang Katipunan! Mabuhi ang Santo Niño!” (Long live the Katipunan! Long live the Santo Niño!).

After the Philippine-American War, the nationalist Iglesia Filipina Independiente, also known as Aglipayan Church, attracted a number of followers. This was brought about by the disenchantment of patriotic Filipinos in the friars and the failure of the secularization of churches in the Philippines. Among the leading supporters of the Aglipayan church was Ternate, Cavite, whose patriotic Municipal Government officials seized the keys of the Ternate Church from its Spanish parish priest. According to these officials, the Ternate Catholic faithful had the authority over the Ternate Church and the Santo Niño image brought by their ancestors from Indonesia.

Another instance of the link between the Santo Niño and the Katipunan was cited by National Artist Nick Joaquin. Joaquin once wrote that it was a custom during the feast of Santo Niño in Tondo for women to wear “Katipunera” attire, consisting of a red blouse, white shirt, and a peasant’s hat.

The Santo Niño in the Time of Naruto

For several centuries, the Santo Niño has been part of the Filipinos’ everyday life. Its image can be seen today in jeepneys, UV express vans, inside the bag of board exam takers, on the altars of homes, airport lounges, and offices. Filipinos also love to dress up the Santo Niño according to them in various professions and personalities: as a police officer, a press member, security guard, tailor, chemist, beggar, and Naruto.

Today, devotees regularly flock to the feast of the Santo Niño. The feast day of the Santo Niño is usually celebrated in January. Ternate celebrates first every 8-9 January. Cebu and Tondo come next every third Sunday of the month. While Iloilo City—where the Santo Niño feast is called the Dinagyang—celebrates every fourth Sunday of January.

It is neither surprising that the Santo Niño had a place in big celebrations of the Catholic Church in the past, such as during the 3rd National Eucharistic Congress held in time for the 400th anniversary of the Christianization of the Philippines from 28 April – 2 May 1965; and the 51st International Eucharistic Congress on 15 January 2016, both events held in Cebu.

About the Author

MICHAEL CHARLESTON “XIAO” CHUA is a public historian and Assistant Professorial Lecturer of History at the De La Salle University Manila. He is the author of a number of refereed academic journals and a columnist at the Manila Times and Abante. He was the creator of Xiao Time, the history segment of the government television station.